Letting animals be animals: An elephant and the evolving role of zoos

Letting animals be animals: An elephant and the evolving role of zoos

From breakfasts with orangutans to protected contact with elephants, Temasek portfolio company Mandai Wildlife Group has sharpened its focus on animal well-being and conservation

animal and plant species globally are threatened with extinction, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

But something meaningful is taking shape in Singapore – and it just might offer hope.

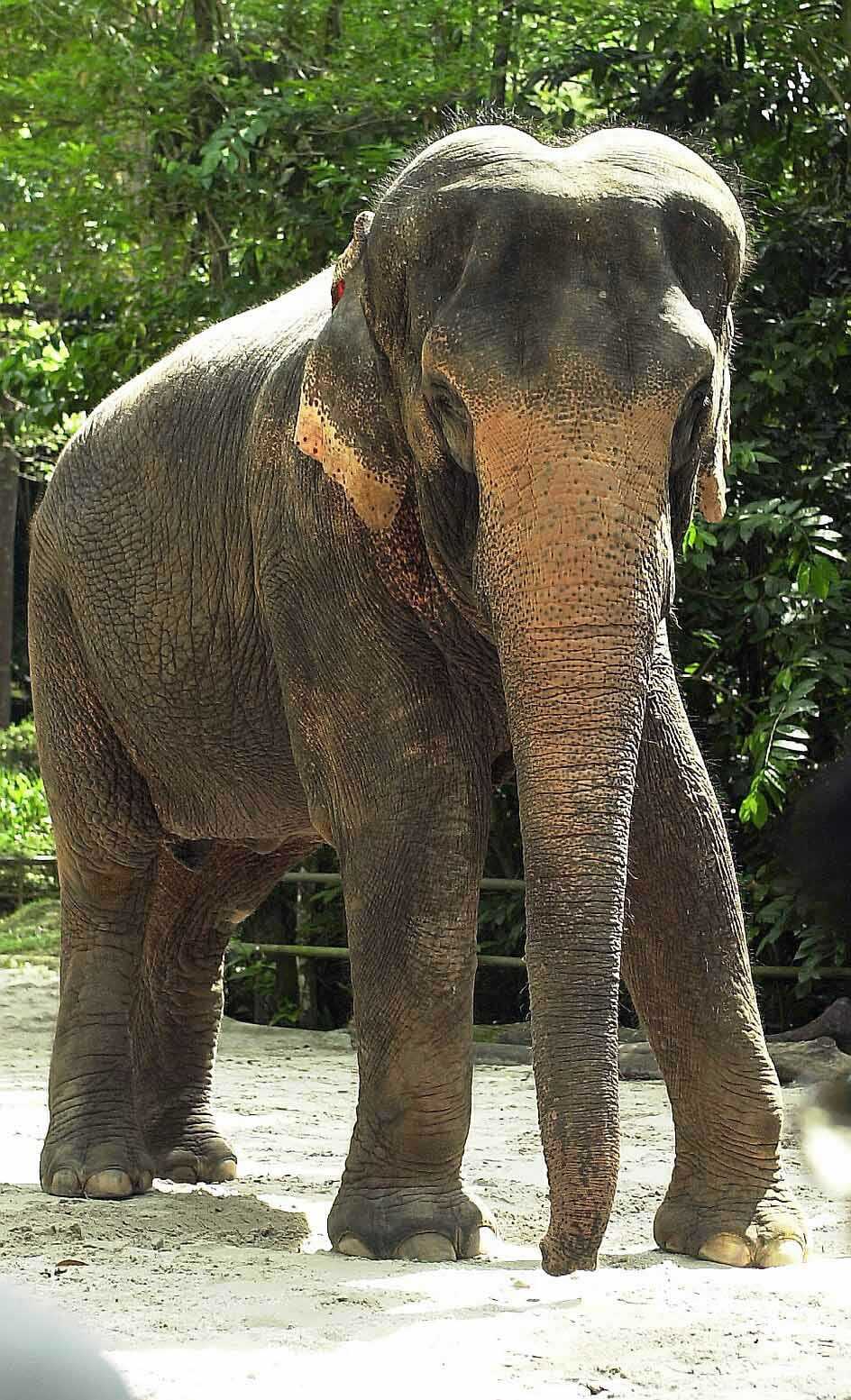

It starts with relationships. Like this one between an elephant and a human.

Image courtesy of SPH Media.

It was a rainy afternoon in 2005, and they were indoors. Mr Saravanan Elangkovan was sitting on a stool when Komali, a 2,885kg Sri Lankan elephant, sauntered over and towered over him.

It was a gesture similar to what elephants do to protect their young.

And it was a breakthrough; a bridge had finally been built between human and animal. There was no command or cue. She had simply chosen to be near.

Their relationship, which began in 1997, hadn’t always been this way.

Image courtesy of SPH Media.

She used to keep me on my toes almost every day, says Mr Saravanan, who was 21 and a junior keeper when he first met Komali. Then about 55 in elephant years, Komali was showing signs of dominance. She had been brought here as a calf from Sri Lanka’s Dehiwala Zoo

“Every time I walked past her, she’d be staring. Then her ears would go back; when you get closer, she’d start to kick.”

Back then, elephant care was grounded in hierarchy: Keepers were taught to be the alpha – firm, always in control – to train elephants and earn their respect.

“Komali was a tough nut to crack,” says Mr Saravanan, now 49 and vice-president of Animal Care (Operations) at Mandai Wildlife Group. “She’s got a very strong character. The first five years were tough.”

To Mr Saravanan, that rainy afternoon felt like the start of something different: A relationship not defined by who was in charge, but built on respect.

It reflected a wider shift at Mandai Wildlife Group, one that would reshape how all animals are cared for, and the ideal of a modern zoo – to advance not just animal care but also wildlife conservation.

Different ways to care

Today, caring for animals at Mandai Wildlife Group’s wildlife parks involves a deeper focus of their physical, behavioural and mental well-being.

The approach is reflected across the group’s five parks within the Mandai Wildlife Reserve: the Singapore Zoo, Night Safari, River Wonders, Bird Paradise and Rainforest Wild Asia, which opened in March 2025.

Rainforest Wild Asia, Mandai Wildlife Group’s adventure-based park, takes visitors through South-east Asia’s rainforest terrain while highlighting regional conservation efforts. Image courtesy of SPH Media.

What you can do at the Mandai Wildlife Reserve – and why it matters

At the Mandai Wildlife Reserve, visitors can see some 21,000 animals, stroll along a 3.3km public boardwalk, stay in a rainforest resort and soon explore nature-themed indoor experiences.

Why bring everything here? It’s part of a broader Mandai transformation.

Having all the parks in one site allows for better use of crucial resources, from specialised equipment at the avian and animal hospital to quarantine facilities, explains Mr Mike Barclay, group CEO of Mandai Wildlife Group. It also offers a more seamless experience for visitors.

In 2023, after a year of planning with its shareholder Temasek, Mandai Wildlife Group relocated 3,500 birds across 400 species. The move from Jurong Bird Park to Bird Paradise took about four months, with the birds transported in padded crates and air-conditioned trucks.

The Singapore Zoo and Jurong Bird Park were part of the Singapore-headquartered investor Temasek’s original portfolio when it was established in 1974.

When Temasek was invited to reimagine the land next to Mandai Wildlife Group’s existing parks, it saw an opportunity to build on the group’s reputation as a pioneer in nature-based attractions, says Ms Teo Hui Keng, director of Temasek’s Portfolio Development Group.

The goal? To shape a destination that’s environmentally and financially sustainable, where people can connect with nature and wildlife.

The result is one of its most ambitious projects with Mandai Wildlife Group – transforming a 126-ha site, about the size of over 170 football fields, into an integrated nature and wildlife destination.

Temasek assembled a dedicated team to help conduct consumer research, consult experts and engage stakeholders to shape the vision that could “redefine the industry”, she adds.

“By creating a vibrant and sustainable destination, we sought to achieve more than business growth,” says Ms Teo, but “to also amplify wildlife and biodiversity conservation efforts, aligning with Temasek's broader mission of promoting a sustainable future for generations to come.”

Mandai Wildlife Group saw a 54 per cent year-on-year growth in attendance in the financial year ending 31 March 2024, with a total of 4.43 million visitors. One million of them came from Bird Paradise.

Mandai Wildlife Group sustains itself primarily through earned income, with admissions and rides contributing about 70 per cent of its $194 million revenue.

“The growth of Temasek’s portfolio companies from local to regional and global leaders reflects Singapore’s pioneering spirit and its DNA of determination, innovation and vision.

“As an active shareholder, Temasek engages them to enhance shareholder value as they grow their competitive edge and generate sustainable long-term returns, while fostering meaningful change for people and communities – so every generation prospers.”

– Mr Dilhan Pillay Sandrasegara, executive director and chief executive officer, Temasek

Our Singapore DNA, a series in partnership with Temasek, spotlights how home-grown companies in its portfolio have grown into regional and global leaders. It also explores how Temasek has partnered them throughout their journeys.

One of the most visible changes is the use of “protected contact”, where keepers no longer share the same space as larger animals like elephants, and instead interact with them through barriers. And rather than performing tricks, animals are encouraged to cooperate in health checks with treats and praise.

It’s a shift in stark contrast to the era of Ah Meng, the zoo’s beloved orangutan known for her breakfast sessions with guests. From 1982 until about 2005, guests could dine alongside the gentle-natured ape. She died in 2008.

Ah Meng, the zoo’s beloved orangutan, was known for her breakfast sessions with guests. She became the first and only animal to receive the Special Tourism Ambassador award in 1992. Image courtesy of SPH Media.

“Our approach to animal presentations and programmes has evolved significantly over the years,” says Mr Mike Barclay, group CEO of Mandai Wildlife Group.

“In the past, like many zoos, some shows included animals performing tricks, which was common at the time,” he says. “But as our understanding of animal welfare deepened, we made a conscious decision to change.”

Now, animals decide how and when to interact, says Mr Saravanan. This autonomy lets them behave more naturally.

Mandai Wildlife Group's approach to animal presentations and programmes has evolved over the years as its understanding of animal welfare deepened, says group CEO Mike Barclay. Image courtesy of Mandai Wildlife Group.

At the heart of this change is the Five Domains of Animal Welfare: Nutrition, environment, health, behavioural interactions and mental state.

The framework, adopted by Mandai Wildlife Group in 2016, provides “a full picture of what good animal welfare really means”, says Mr Barclay. It’s not just about keeping them healthy, but also encouraging their natural behaviours.

How to tell when they're well?

The Five Domains of Animal Welfare is a globally recognised framework that helps assess animal well-being – not just physically, but emotionally too.

It guides how Mandai Wildlife Group cares for animals across its parks.

Image courtesy of SPH Media.

Nutrition: Is the animal eating well? The right diet also depends on the species. For instance, not all monkeys should eat ripe bananas. Leaf-eating monkeys known as Colobines, like François’ langur (pictured) and proboscis monkeys, are not used to a high-sugar diet in the wild

Image courtesy of SPH Media.

Environment: Is the space safe and suitable to their needs? The Singapore Zoo, for example, features the world’s first free-ranging orangutan habitat with tall trees, foliage and vines to mimic their natural environment.

Image courtesy of Mandai Wildlife Group.

Mental state: The other four domains – nutrition, environment, health and behaviour – all influence the animal’s mental state. Good welfare means animals feel safe, calm and curious, and not stressed or bored.

Image courtesy of SPH Media.

Behaviour: Can the animals act naturally? Beyond enrichment programmes, mixed habitats – where compatible species like gibbons and orangutans share the same space – allow animals to interact with other species and encourage natural behaviours such as foraging, socialising and exploration.

Image courtesy of Mandai Wildlife Group.

Health: Are they getting the care they need? Regular health monitoring is essential. Keepers at Mandai Wildlife Group use positive reinforcement – like treats and praise – to help animals stay calm during these checks.

That philosophy extends to feeding. Elephants like Komali used to be offered mostly fruits by visitors. Those are now reserved as occasional treats. Their main diet includes a wide variety of vegetables and dried food like hay.

Komali and Jati, her best friend, seem content with their new menu. When The Straits Times met Mr Saravanan, the elephants were gently picking cabbages from guests’ hands with their trunks.

Automated feeders also release food at different points around the habitat to encourage movement and foraging. Schedules are varied to reduce “anticipatory behaviour” like pacing, says Mr Saravanan, which could affect well-being.

Beyond the zoo

The broader purpose – of not just improving animal well-being, but also wildlife conservation and public education – extends behind the scenes.

Number of international breeding programmes Mandai Wildlife Group participates in, including for threatened species like the black hornbill and Malayan sun bear

Mr Saravanan coordinates animal transfers and breeding programmes with zoos around the world, including the South-east Asian Zoo and

Aquarium Association (Seaza) and the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (Eaza).

Through its parks, Mandai Wildlife Group focuses on creating impactful wildlife experiences, engaging visitors and raising conservation awareness.

Meanwhile, its conservation arm Mandai Nature – part of Temasek Trust’s non-profit ecosystem – leads efforts with partners to protect wildlife in their natural habitats in South-east Asia. These include conservation experts, non-governmental organisations, educational institutions and local communities.

Evolution of the zoos

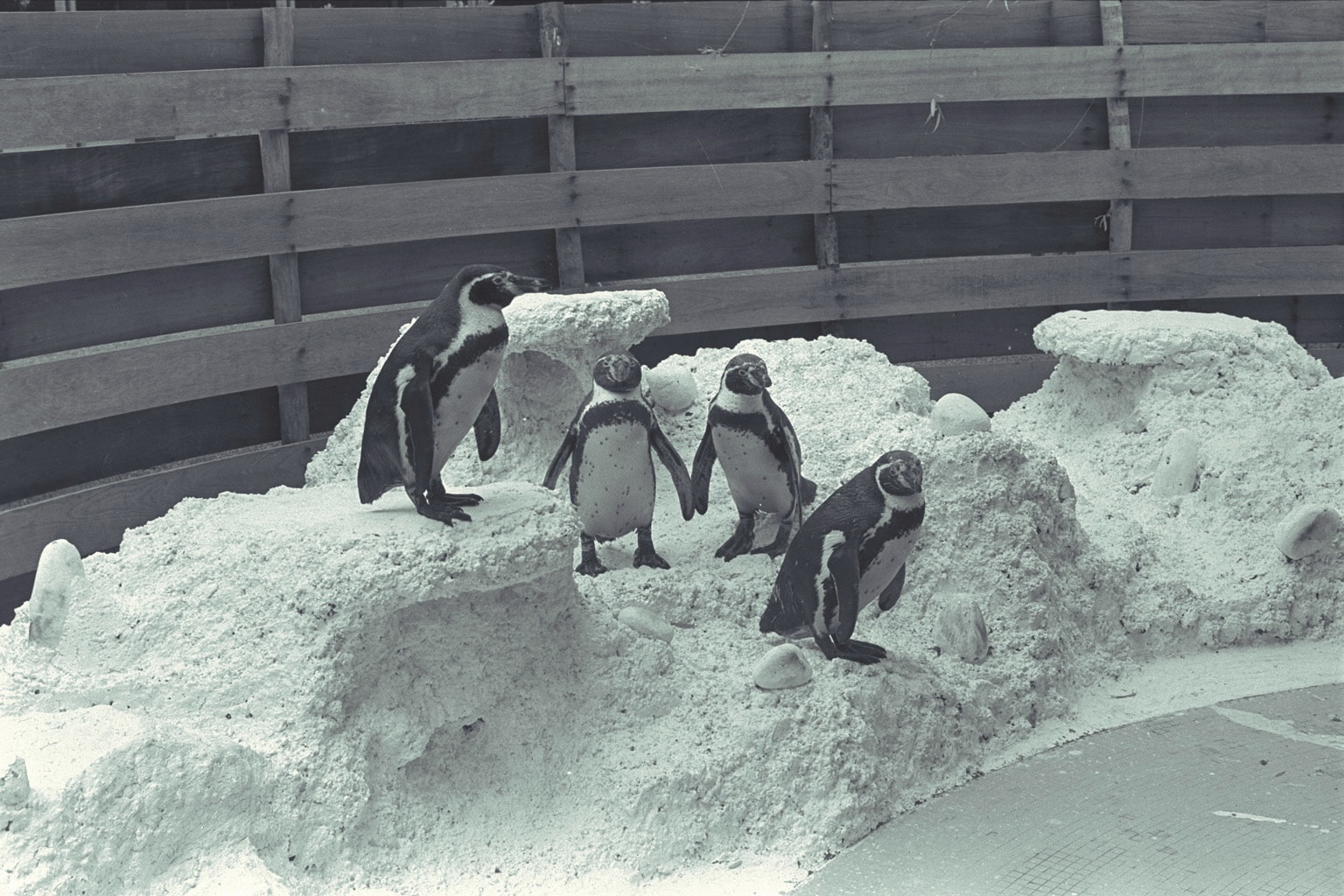

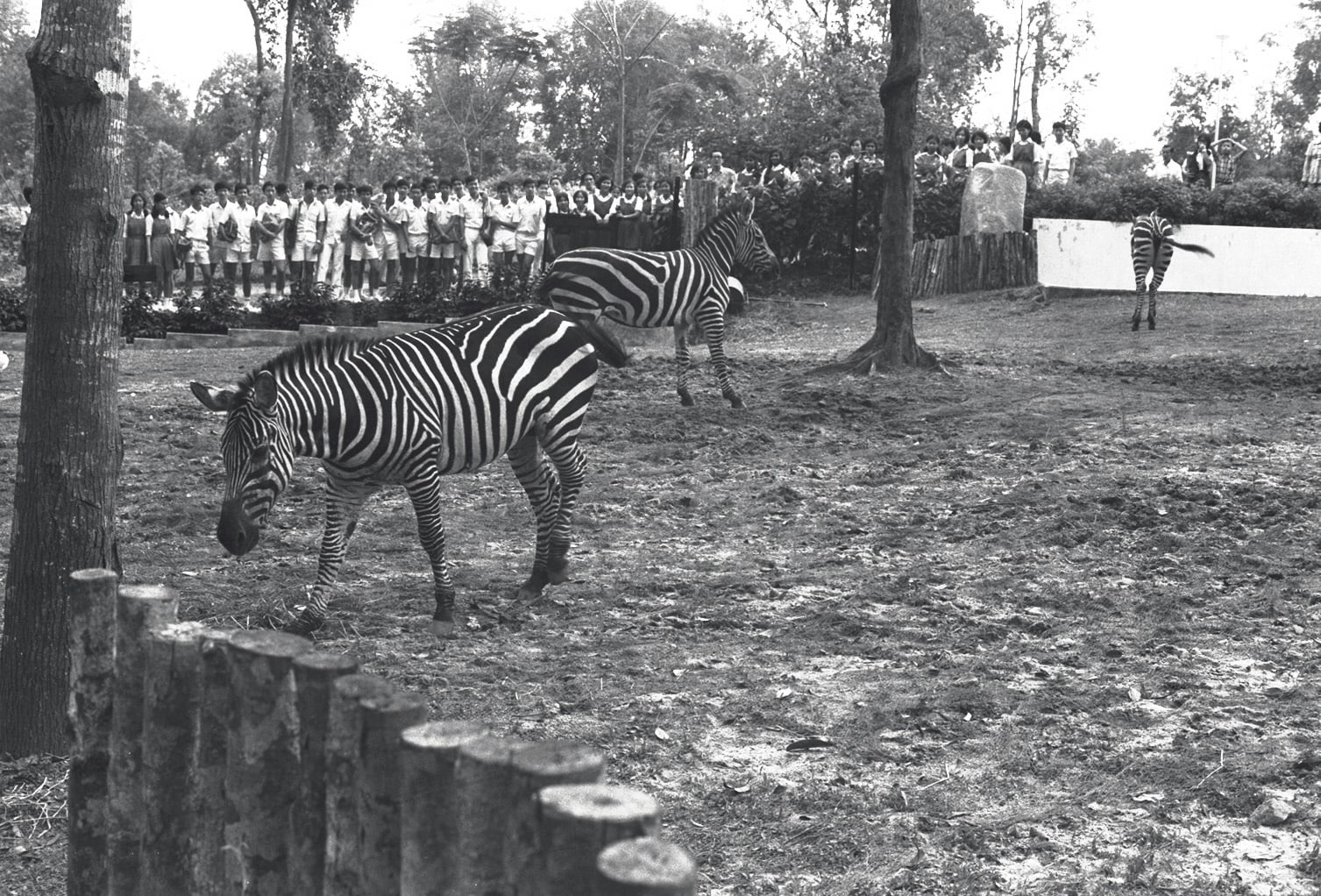

1971 - 1988

Image courtesy of SPH Media.

1973: Singapore Zoo (formerly known as Singapore Zoological Gardens) opened in June. The open-concept zoo housed about 300 animals across over 70 species, including the late Sumatran orangutan Ah Meng.

Image courtesy of SPH Media.

1971: Jurong Bird Park (now known as Bird Paradise) opened in January with more than 5,000 birds across 400 species. It was Asia’s largest bird park at the time.

Image courtesy of SPH Media.

1988: Jurong Bird Park established a Breeding and Research Centre to support the conservation of rare and endangered birds. The centre was opened to the public in 2012 to raise awareness of conservation and breeding efforts.

1994 - 2014

1994: Night Safari, the world’s first night zoo, opened in May. The Night Safari, which also features an open concept, showcases nocturnal tropical animals, with lighting made to imitate moonlight.

Image courtesy of SPH Media.

2014: River Wonders (formerly known as River Safari) officially opened, spotlighting freshwater ecosystems and species. It is home to the two giant pandas – Jia Jia and Kai Kai – on loan from China. Jia Jia gave birth to a male baby panda named Le Le in August 2021, who returned to China in 2024.

Image courtesy of SPH Media.

2009: The Wildlife Reserves Singapore Conservation Fund was established to support research and deepen knowledge of local biodiversity. It has evolved into Mandai Nature, Mandai Wildlife Group’s conservation arm established with Temasek. Mandai Nature is now part of Temasek Trust’s non-profit ecosystem.

Image courtesy of Mandai Wildlife Group.

2018 - 2025

2018: Mandai Wildlife Group was officially accredited by the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (Eaza) and the Zoo and Aquarium Association of Australasia (Zaa), paving the way for deeper participation in breeding programmes across the two regions.

Image courtesy of SPH Media.

2025: Rainforest Wild Asia opened in March with 36 species. About three in four species in the adventure-based park are threatened with extinction, including the Malayan tapir and Francois’ langur – one of the world’s rarest monkeys with just 2,000 remaining in the wild.

Image courtesy of SPH Media.

2023: Jurong Bird Park officially closed in January after 52 years. Its 3,500 birds were moved to Bird Paradise, which opened in May at the Mandai Wildlife Reserve.

A portion of Mandai Wildlife Group’s revenue goes to Mandai Nature, which contributed over $4.5 million to biodiversity conservation in the financial year ending 31 March 2024.

One such success: the Rote Island snake-necked turtle. Once thought to be extinct in the wild, 23 of the critically endangered species were brought to Singapore in 2015 to form an “assurance colony” – a back-up population. The turtles came from breeding facilities in the US and Austria.

Image courtesy of Mandai Wildlife Group.

In 2021, the zoo-bred turtles were repatriated to a conservation breeding facility on Indonesia's Rote Island through a joint effort between Mandai Wildlife Group, Mandai Nature, the Indonesian government and Wildlife Conservation Society Indonesia Programme (WCS Indonesia). By 2023, they were nesting.

Number of conservation projects supported by Mandai Nature across Asia

Mandai Wildlife Group’s parks also serve as a research and training hub, helping to build expertise in veterinary and animal care.

“By protecting wildlife in their natural habitats and providing a safety net for these species within our zoos, we work together to ensure their survival both in the wild and in human care.”

– Mr Mike Barclay, group CEO, Mandai Wildlife Group

Komali may not have grown up in a world with five welfare domains, but she’s helped people better understand animals – just by being herself.

Will young keepers today build the same bond that Mr Saravanan has with Komali – the kind that comes from close physical proximity?

“Ultimately, it's how you express your love,” says the father of three sons. Animals are highly perceptive, he adds; they’ll even try to cheer you up if they know you’re having a bad day.

When Mr Saravanan visits, Komali and Jati still reach out to him with their trunks, with their ears flapping and a soft rumble in their chests. Not asking for food – just greeting a familiar friend.

Image courtesy of SPH Media.

“That’s 28 years of relationship there,” says Mr Saravanan, wistfully.

Their connection reflects the shift in modern zoos: That care and conservation begin with relationships – with animals, people, and the world we share.

“We are proud to welcome millions of visitors from Singapore and around the world, but our real goal is to inspire a deeper connection with wildlife and a stronger commitment to conservation,” says Mr Barclay.

“When people connect emotionally, they’re more likely to care,” he adds. “And when they care, change becomes possible.”

Our Singapore DNA spotlights how home-grown companies in Temasek's portfolio have grown into regional and global leaders. The series also explores how Temasek partners its portfolio companies throughout their journeys.

In partnership with

Source: The Straits Times © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.